I recently was online and saw a tee shirt imprinted with a quotation from hymnody reading “it is well with my soul!” And I thought to myself, “it is not well with my soul right now.” After breaking up with my partner of four years, losing my best friend and aunt, my grandfather a week later, and going through an arthritis infusion switch, I was very unwell indeed.

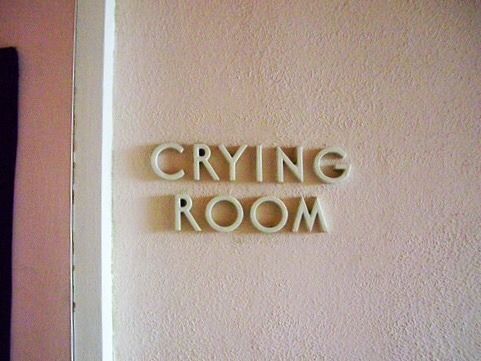

What happens when we answer the question how are you? with honesty? What happens when it is not well with our souls? When we are living in Lamentations? What is the antidote to a hurting soul and heart in a trite and disingenuine world?

I had a co-worker ask me if I enjoyed my bereavement leave and I answered a little too honestly. We grant people a weird death vacation, and then expect them to return back to normal in bodymind, ready to be productive to the system, be useful to us, and no longer inconvenient grievers feeling feelings that cause others discomfort.

I’m sorry for your loss.

If we were only able to sit in the discomfort for a moment with somebody else, maybe we could stitch a soul just a tiny bit. Maybe we could sense the gravity of someone who lost the rest of their family in a mere month. Maybe we could steady someone who’s heart is quivering, trying to make it.

As someone who has now experienced eight losses in two years, I wish I had something mystical and profound to say about grief or healing or seasons. Something lyrical and mending. All I have found is that life goes on without them, and Lamentations 1:20 feels viscerally true when it says: “See, LORD, how distressed I am! I am in torment within, and in my heart I am disturbed, for I have been most rebellious. Outside, the sword bereaves; inside, there is only death.” Being surrounded by death, having death cover your house is a very real, palpable feeling. Rebelling to me doesn’t mean acting out or doing something incorrectly, but feeling wildly, and bigl-ly.

Nicholas Wolterstorff is onto something in his writings when he describes grief as sitting on a mourning bench alone. When we invite our divinity figure, they can sit there next to us on the mourning bench, so we are no longer alone. When we look at this kind of incarnational relationship, we see a God(dess) who seeks to intimately know us in our pain, who is also bereaved for us, who feels deeply. Some scholars call this divine omnisubjectivity, or put simply “omni-empathy”- perfect divine empathy. We are not meant to mourn alone, but in community. Even a pair is community.

Every time I remember them again, I lose them again, I invite God to sit with me on the bench. Every time I cry in the car, God cries next to me. When I rage, Christ rages beside me. My soul is not well, and that is fine with God.